Explore the outside walls of Uptown Butte buildings to view a window into the past when businesses vied for the privilege to cover their own or their neighbor’s walls with commercial messages for their products and services.

Butte still has close to 100 of these commercial painted signs on the walls of its remaining historic buildings from Front Street to Walkerville, some nearly faded away. They are worth a visit to get an insight into the numerous businesses that once proudly announced their products and services in fresh paint. If you look closely, you will see that some have been painted over several times, another indication of the busy commercial district and the precious real estate that these wall spaces represented.

Since 1999, Mainstreet has worked to preserve these ghost signs as an important part of our heritage. Since they are the property of the building owners, they are at the mercy of modern-day decisions. Some have been lost to low-cost painting jobs and demolition or just the simple consequences of inattention and time. Fortunately, many building owners see the value of preserving these portals into our past and have taken steps to preserve these commercial messages on their buildings.

Some have proposed that these signs should be allowed to fade away or be captured in an advanced state of decay using a chemical coating that freezes the process in time. These approaches, to leave them alone and let the elements have their way and allow them to disappear, or to freeze them in the beauty of decay forever, are not supported by the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Technical Brief 25 “The Preservation of Historic Signs” or clearly recommended in other professional recommendations. In fact, treatment approaches are a matter of aesthetics, subjective, and open to interpretation by anyone with an opinion in any given community and usually the final word is that of the property owner.

Like buildings, if these signs can be preserved or restored, they should be. In fact, several of these signs in Butte’s historic district have been carefully restored or repainted to ensure that they remain sentinels to Butte’s past despite modern uses for the buildings. Ironically, for example, one blog about why these signs should not be touched uses an example image of a sign that Mainstreet Uptown Butte helped to restore to prevent its disappearance.

One small parcel of common ground in the debate is the belief that each sign should be evaluated on a case by case basis before any action is taken. It’s a complicated issue, but, as with historic buildings, that should not be an excuse for inaction which has a predictable result in both instances, the loss of a historic resource that could have been preserved or restored when there was still time to act and is now gone.

When Mainstreet first sought guidance from experts around the country including the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2000, one recommendation was a national network of muralists and sign restoration specialists known as The Walldogs — www.thewalldogs.com. The Walldogs have the rare expertise and experience of working with both paint and historic brick and know how they work together in historic wall signs. Picking up where this project left off in 2000, Mainstreet established contact with the Walldogs in 2012 and brought them to Butte with the assistance of the Montana Main Street program and the Butte-Silver Bow Historic Preservation Office.

The effort continues to bring attention and interpret these historic signs to enhance the experience of a historic tour of Uptown Butte. If you would like more information or to help support this effort with your tax-deductible contributions, contact the BSB Historic Preservation Office at 406-497-6258 or send contributions to be applied toward a fund for their preservation and restoration to Butte’s Ghost Signs, c/o Mainstreet Uptown Butte, P.O. Box 696, Butte, MT 59703.

Here then are more than 20 prominent commercial wall signs from the streets of Butte, a fraction of those that remain on Uptown walls. They are clustered within the traditional central business district in close proximity to one another; well worth an hour or so of your time to walk or drive to see them and receive a message that was placed there more than a century ago, long before digital signboards, billboards, Facebook and Google ads, hoping to snag the attention of a potential customer like you. Tour them and join in the debate about how best to preserve them for future generations or see them before they are gone and just enjoy them for what they represent in the here and the now while they last, a fascinating portal to Butte’s rich business history.

1. Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum

Alley behind 83 E. Park Street

This wall ad for Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum in the alley behind 83 E. Park Street was probably placed on this wall to be visible from the McDermott, or, after 1902, the Finlen Hotel across the street. The four-story tall ad proclaims that “The flavor lasts” as does the bright green paint on the north-facing side of the building that is still evident decades after the ad was painted on the shaded wall. The Wrigley company began selling and advertising its spearmint gum in 1893. The packet label reads PEPSIN GUM which dates the design between 1893 and 1913. The paint has faded enough to reveal an earlier sign that is visible under the chewing gum ad.

Look for the W next to the pack of gum and let your eye put it together for you. The ad underneath is for Elgin Watches, indicating that wall space was at a premium in the hectic Uptown district.

There has been damage to the bricks of the wall in the lower left by delivery trucks entering the narrow alley. The bricks have been restored but the sign has not. The sign should be restored to repair the rest of the ad that reads Buy it by the box.

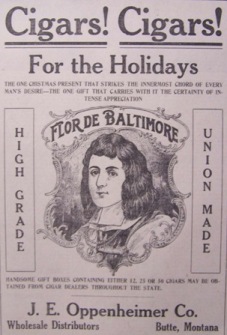

2. Flor de Baltimore

12 S. Main St. and 521 W. Park St.

This wall ad is visible in the drive-through of US Bank at 10 S. Main Street. It was painted on the north side of the Iona Cafe to advertise popular cigars — The Peer of Havana Cigars – Flor de Baltimore. A second Flor de Baltimore sign is still visible on the west wall of Vu Villa Pizza at 521 West Park Street. Havana was a type of tobacco grown in the US, by the way, and did not necessarily indicate that the cigars were from Cuba. Flor de Baltimore was touting its high quality and the fact that the tobacco was high quality as cigars made from Havana tobacco.

Flor de Baltimore was a popular brand imported from Baltimore by way of Salt Lake City at one time exclusively by J.E. Oppenheimer, the brand’s sole distributor in Butte.

In 1886, Baltimore boasted 640 cigar factories. Approximately 60 other Baltimore factories made cigarettes, chew and smoking tobacco. Impressive but tame compared to Manhattan which had 1,940 cigar factories in operation that year.

According to the National Cigar Museum, in 1896 Americans smoked about 7 billion cigars. Worldwide, the number of cigars consumed that year is estimated at 40 billion.

In a city populated mostly by single miners who enjoyed themselves when they were not underground risking their lives to get “the rock in the box,” cigars were an inexpensive but significant expenditure in Butte for leisure and, for many, a necessity.

In 1900, the Polk Directory listed 10 cigar manufacturers in Butte. There were eight cigar wholesalers and 26 retail cigar stores. Also in 1900, Butte union membership numbered 18,000 and among them were many members of the Cigar Makers International Union of America No. 361.

The term cigar store took on a special meaning in Butte with the passage of the Volstead Act in 1919 and the onset of the Prohibition era. Butte bars that previously touted whiskey and beer, such as the Crown and the M&M became cigar stores overnight. The name was the only change in their operation. Suddenly, you could purchase a fine cigar and Sean O’Farrell to drink would magically appear.

This image of the Elk built in 1916 at the intersection of Broadway and Main reveals a Flor de Baltimore billboard.

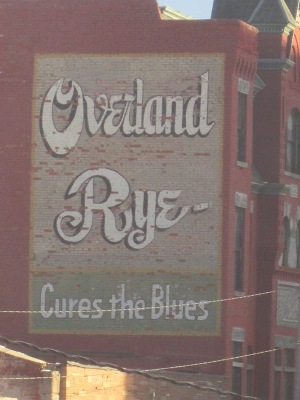

3. Overland Rye Whiskey

15 W. Park St.

Overland Rye Whiskey of Idaho Falls, Idaho advertised on the west wall of the Curtis Music Hall that it cures the blues. It did not help Jim Ledford. This sign is visible from the west driving east on Park Street. Spalling brick is starting to impact the integrity of the sign.

The tall ad may be the result of a connection with the Ledford brothers, William and Jim, of Polk County, Tennessee. Jim was born in 1848 in Polk County, Tennessee. In 1878 he, his brother, a cousin and others left the copper mining industry there to go to Leadville, Colorado’s mines. They stayed in Leadville until 1889 when they went to Butte, Montana. By 1903 Jim was in Idaho Falls where until 1913 he owned and operated the Montana Saloon on the corner of 2nd and Capital Streets.

Jim had legal troubles that prompted his return to Butte. He went back to Butte, had his wife sell his property to pay his bondsmen. He operated a mercantile/cigar store in Butte until 1928 when he was shot in the back of the head during a robbery.

When brother Jim wrote home to Tennessee, he used letterhead from the Overland Rye Company.

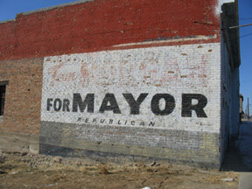

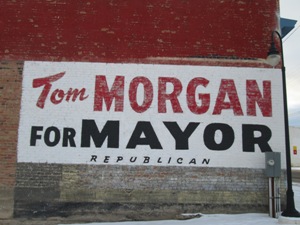

4. Tom Morgan for Mayor

56 E. Mercury St.

This sign is rare – a political ad that has survived the years-long after the campaign and the life of the candidate. The ad was for a Republican candidate for mayor (a position that no longer exists — Butte now has a Chief Executive for a consolidated city and county government). Tom Morgan was one of nine mayors who ran on the Republican ticket. He served from 1949 through 1953.

What else is rare about this sign? Mainstreet Uptown Butte received permission from the property owner in 2005 to restore the sign when it was obvious that the red paint of Tom Morgan’s name was nearly illegible. The sign was carefully restored by professional sign painter John Weitzel with its original colors. The image above, taken in December 2012 shows that the sign like all things has aged in the few years since it was restored.

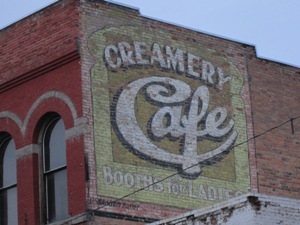

5. Creamery Cafe “Booths for Ladies”

19 W. Broadway

Theo McCabe and Roy McClelland both came to Butte in 1903, and in July of that year, they partnered to establish a restaurant at 36 North Main Street. When a devastating fire destroyed the restaurant’s original location, they moved down around the corner to the Mantle and Bielenberg Building which remained the home of the Creamery Cafe from 1913 until 1957.

The Creamery Cafe wanted unescorted women to know that they could dine there without the fear of being molested during their meals. The phrase Booths for Ladies can be found in ads for restaurants from Connecticut to San Diego, California.

According to Mary Murphy in Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters, “I would say that “Booths for Ladies” was a fairly common advertisement to see in early 20th-century cafe, parlor, and saloon windows…There is the interpretation of the signage to mean the business offers the service of protection from their own rowdy bar crowd, possible public humiliation in the confrontation of the male customer’s drunken verbal abuse. I believe this service or selling point, could be more common in the western united states, where dangerous behavior bred in the boomtown saloons. The most common sense reasoning for me is that a true lady of the times should not be expected to sit on a stool at the counter, instead she should be offered the comfort and grace of private booth seating while she dines.”

6. Silver Bow Paint

43 W. Broadway

This wall ad for the Silver Bow Paint Company was painted on the west corner of the Hamilton Block to capture the attention of travelers heading east. Structural issues with the brick on the wall and the deteriorating cornice indicates that there is much work before this sign can be preserved or restored.

7. The Kenwood (Sullivan Plumbing and Heating)

63 W. Broadway

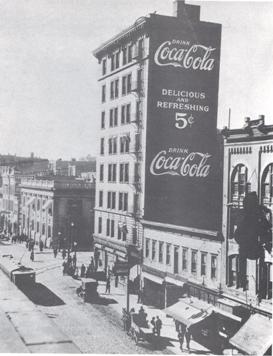

This large sign indicating the location of a plumbing and heating business endures long after that business has disappeared. Most recently, this building has served as the headquarters for Pioneer Technical Services, which chose to leave the sign undisturbed. If you look closely however you will see that Sullivan Plumbing and Heating was not so sensitive and painted their sign over top one of Broadway’s early Coca Cola signs. This would present another interesting dilemma for a restoration effort. Do you bring back the older Coca Cola sign at the same time or not?

8. The Grand Hotel

124 W. Broadway

This east-facing wall was used to advertise the services of an HVAC contractor, the Harry L. Hanson Co. as well as the fact that it was a hotel. The building is now home to the Quarry Brewing Co. in the basement. The Grand is located a half-block from where the Broadway Theater (later the Montana Theatre) stood and housed many of the vaudeville entertainers that performed there, including Jimmy Durante, who was reported to have stayed in Room 202.

The Grand Hotel was originally designed to serve as a labor temple, but was acquired during construction by U.S. Sen. Burton K. Wheeler in exchange for legal services provided to the trade unions and became known as the Wheeler Block. Wheeler came to Butte on his way to Seattle and lost all of his money in a poker game and was forced to stay in Butte. As a lawyer, and then Montana’s U.S. Attorney from 1913 to 1918 appointed by Woodrow Wilson, Wheeler opposed the violation of civil liberties during the martial law years. In 1920, he ran for Governor and lost, and then in 1922, he was elected to the U. S. Senate to represent Montana. As a Senator, he went on to become a political rally, and then foe of Franklin Delano Roosevelt when he spoke out against efforts to stack the U.S. Supreme Court and to oppose America’s entry into World War II.

9. Lutey’s Grocery Co. Marketeria

146 W. Park Street

This sign marks the spot of one of Butte’s most innovative small businesses, Lutey’s Marketeria at 146 W. Park Street. At one time the Luteys had 11 stores in Butte. Noticing the rising costs of horse-drawn deliveries and the trend toward self-serve cafeterias like the Purity Cafe on Broadway, the owners opened a self-serve grocery store on February 7, 1912. That same year they distributed a manifesto of sorts titled Cutting Out the Frills. In it they wrote, “We believe the time is at hand when all thoughtful customers will cooperate with merchants and will help in cutting out the frills so as to afford a lower cost of living.” They patented the idea and name of the Marketeria and the Groceteria in 1913.

Sons of founder Joseph Lutey, Sr., Joseph Lutey Jr., and William J. Lutey, decided to make the change the year after their father died. Before that, shoppers were used to visiting an ordering store on West Park and placing an order for home or business delivery. A warehouse on Galena Street then dispatched deliveries throughout the city and surrounding region. That building was also used for a bakery and to roast coffee. The Lutey brothers bet that shoppers would prefer to carry home their own groceries and save the cost of delivery. The Lutey’s Marketeria became the model for the Piggly Wiggly chain of stores in the south that took the self-service grocery store to a much larger scale. An Irish boycott of their stores to protest their sale of English goods during World War I harmed their business but more damaging to their business was the downturn in copper prices in the 1920s that convinced them to move their enterprise to Seattle and the brothers closed their business in 1924.

10. East Wall of Stephens Hotel

(Highlander Beer and mosaic of other ads)

This wall is an example of a mosaic of previous signs that would be impossible to do justice by with restoration. It may be better suited to a UV protective coating or just being left alone.

The mosaic is dominated by an ad for Highlander Beer. For more than 50 years, Montanans drank this Scottish Ale from the Missoula Brewing Company called Highlander Beer. First released in 1910, Highlander Beer was made and distributed throughout Montana until 1964.

Now, nearly 50 years later, Highlander Beer has returned. Brewed in partnership with the Great Northern Brewery in Whitefish, Montana, Highlander Beer returns from the Missoula Brewing Company as a finely-honed Red Scottish Ale with a rich ruby color, a light malt flavor and is wonderfully balanced, with a light-hopped finish. In the lower right-hand corner of this mosaic is a clue about Butte business’s past.

11. Bertoglio Highlander

801 S. Utah St.

The clue on the mosaic wall is that Highlander Beer is distributed by Bertoglio McTaggert distributors. If you search the warehouse district of Butte, it won’t be too hard to discover where this beer came into Butte by rail from Missoula. The warehouse district of Butte is full of signs that indicate long-gone businesses that involved transport, storage, and distribution for all sorts of appliances, produce, and durable goods. Butte was a remote outpost but it had five train lines bringing goods to the city from all directions every day and most of these were offloaded in the warehouse district.

Bertoglio Storage and Appliance Co. was one such business that now provides a home for Casagranda’s Steakhouse which decorates the walls of the restaurant with invoices and other correspondence related to the Bertoglio family business.

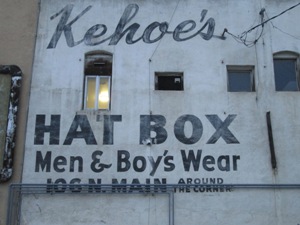

12. The Hat Box

106 N. Main St.

This wall ad marks the waning years of a long-time Butte business that once advertised that they could make a custom hat in three hours. Kehoe’s advertised on the back wall of the company that was entered on North Main Street around the corner.

The Hat Box opened first on 10-12 North Wyoming Street, one block to the east with T.O. Angell as the proprietor. Later it was owned by Ruth and Andrew Kehoe who worked in the business with their children, Drew and Mary, as salespersons.

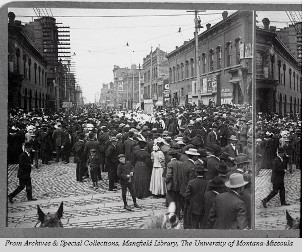

The custom hat business was waning in the 1950s when The Hat Box relocated to 106 N. Main Street here before closing in 1957. In it’s earliest years, hats were required attire for every head in Uptown Butte, including men, women, and children as illustrated by the stereographic image by Norman A. Forsyth at Park and Main during Miner’s Union Day.

Obviously, by the 1950s, fashion had turned toward the bare-headed look and there were many fewer heads in the city that were worth a hat, a trend that unfortunately continues today where the most common head covering is a ballcap.

13. Montana Casket Co.

739 S. Utah St.

This location was marked by a fast-fading painted sign that has outlasted the business of making coffins for Butte’s deceased. The original office was at the corner of Mercury and Wyoming. According to the definitive guide to where the bodies are buried in Butte, Buried in Butte, by Zena Beth McGlashan, the business began in 1935 building caskets and shipping them throughout the region. In the late 1970s, the company was bought out by Inland Casket Company of Spokane.

Today the building is used as an office and warehouse by A&M Fire and Safety, a fire and safety supply store and warehouse, but the ghost sign that remains is a reminder of an earlier business purpose for the storefront.

14. Butte Carriage Works

38 E. Silver St.

A block from Butte High School sits this business that was started by John L. Hurzeler in 1895. A blacksmith by trade, Hurzeler was a founder and partner in the Butte Carriage Works, which quickly grew to become Montana’s largest carriage manufacturer. The business weathered the transition from horses to cars by switching its location and to automobile repairs in the 1920s.

In 1898 they advertised “ Carriage and Sign Painting, Bicycle Enameling and Ornamenting, Done in the Latest Style.” By the early 1920s, Butte Carriage Works moved to 38 E. Silver St., as it outgrew its original location on East Galena and moved down the Hill to East Silver Street to make it easier to provide services to include automobile repair.

15. Mai Wah/Wah Chong Tai

17 W. Mercury St.

These two adjoining buildings remain to help interpret what was once a very busy Chinatown teeming with Asian immigrants, primarily from the Canton area of southern China in a six-block area surrounding Mercury Street. The Mai Wah was a busy noodle parlor and the Wah Chong Tai was an even busier mercantile that served as a Wal-Mart of sorts for Chinese residents of the region. Placer miners would walk into Butte from surrounding camps such as French Gulch and German Gulch to get the latest news, gamble, and acquire Chinese foods and teas.

When it became clear that the mercantile sign was losing its WAH, Mainstreet Uptown Butte helped to restore the painted name signs in 2005 by arranging with artist Eben Goff to carefully hand paint and restore the signs.

The Mai Wah Society is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization established for educational, charitable, and scientific purposes, including research and public education about the history, culture, and conditions of Asian people in the Rocky Mountain West.

The Society collects and preserves artifacts, preserves historic buildings and sites, presents public exhibits, and supports research and publication of materials of scholarly and general interest. For more information, visit www.maiwah.org.

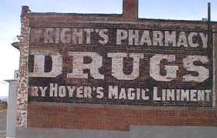

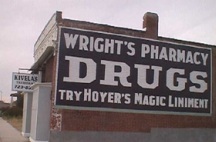

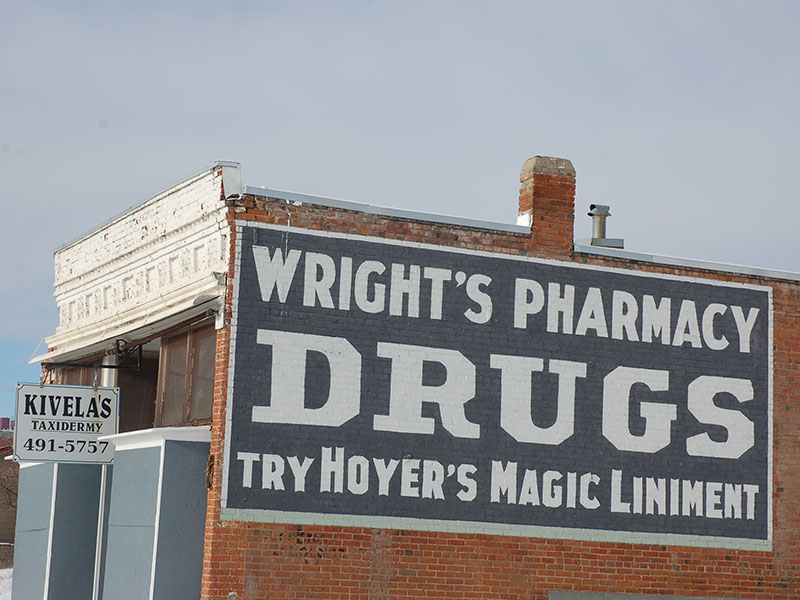

16. Wright’s Pharmacy (Hoyer’s Magic Liniment)

445 E. Park Street

No western town is complete without an early sign for a medicinal remedy that promised to cure the ills that ail you. On the east edge of Butte’s historic Uptown on the last building standing on a city block is a wall ad for Wright’s Pharmacy that touts Hoyer’s Magic Liniment. No record remains of the ingredients of Hoyer’s Magic Liniment but if it was like many others it contained laudanum, morphine and alcohol, the most common ingredients of widely sold palliatives.

This sign underwent a careful restoration in 2005 by the owner to restore the integrity of its border and to guard against the sign fading beyond recognition.

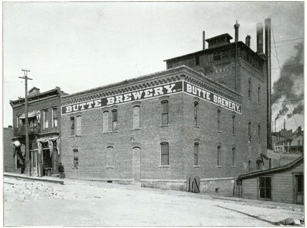

17. Butte Special Beer

205 W. Park St.

The Butte Brewing Company, makers of Butte Beer and Butte Special Beer, was founded in 1885 by German immigrant Henry Muntzer. it was one of five breweries in Butte — the others being the Centennial Brewing Company, the Tivoli Brewery, the Silver Bow Brewery, and the Olympia Brewery.

What follows is an excerpt from Steve Lozar’s excellent work “1,000,000 Bottles A Day: Butte’s Beer History.”

At the end of the Civil War, miners flowed into the area around the Big Butte. Many had grown up in the beer and hop producing areas of Central and Eastern Europe, and they brought with them a love for their familiar lagers, pilsners, bocks, alt-biers, and mead along with the skill to brew it. An influx of Irish immigrants further enhanced the area’s embryonic beer industry. They brought with them their own brewers and favorite recipes for lagers, porters, stouts, and cream ales.

German brewer Henry Muntzer established the Butte Brewing Company in 1885. Within 12 years, he had grown his brewery from a five-barrel-a-day operation to a 50 barrel-a-day plant. T.J. Nerny and John Harrington succeeded Muntzer as owners in the early 1900s. They brought with them the “luck and pluck of the Irish” as they lead the Butte Brewery through the dark days of Prohibition by manufacturing Checo brand soft drinks. After the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the Butte Brewery was the only local brewery to reopen.

Of course, Butte’s German immigrants actively supported their local breweries which advertised extensively in Butte’s three German-language newspapers. The efforts to build brand association even extended to the color of the horse pulling the delivery wagons. If a fellow looked down Park Street at the turn of the century and saw a beer wagon pulled by four or six dapple-gray Percherons, he could be sure the cargo was a fine German-style beer.

If a fellow lived in Dublin Gulch, Corktown, or up the hill in Walkerville, he most likely drank the beer produced at the Butte Brewing Company and delivered in wagons pulled by roan or brown horses. Irish customers had their growlers filled with Dublin Gulch Porter or Eureka Pale as they came off shift and headed home. If an Irish miner was walking down Main Street, he might stop for a stout at Joe Dyers’s New York Brewery. Rounds of “Danny Boy” could be sung while enjoying the beer brewed the California Brewery in Walkerville. Walkerville’s other brewery, the Vienna Brewery, was famous not only for its keg and bottled beer but also for “The Czar,” the “best 12½ cent cigar in the market.” The Scandinavian population of Butte did not boast any homeland brewers. They did, however, enjoy their beer as much as any ethnic group in the metropolis. The Butte Brewery was located closest to Finntown and played a prominent role in the Finns’, Swedes’, and Norwegians’ annual festivities, often hosting impromptu lutefisk-eating and beer-drinking competitions as well as street dancing and bare-fist boxing matches.

Now, Butte is on the verge of having the Butte Brewing Company return to operation and with it the brands of Butte Beer and Butte Special Beer. For details, visit www.buttebrewing.com.

18. Coca Cola on Broadway

102 N. Main St.

Coca Cola purchased privilege signs throughout the country and in a cosmopolitan city like Butte there were several, especially on Broadway which was a major cross city boulevard. There were at least four large Coca-Cola ads on Broadway buildings within two blocks of one another. On the east side of the Hirbour Tower at 102 N. Main on Broadway the red paint has aged to yellow but if you squint, you can still see the large lettering of Coca Cola from the street from what was the tallest wall art in the city at five stories.

The building is in the midst of a major renovation from its use for office spaces in 1901 to being repurposed for modern condo living. The hope is that when the renovation is complete the owners will be able to turn their attention to restoring this sign to its original colors facing east.

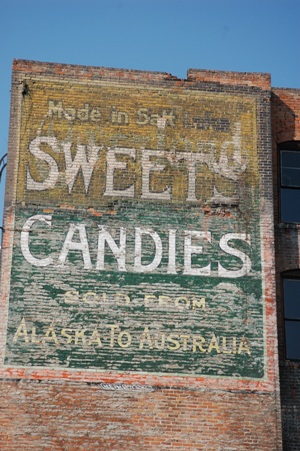

19. Sweet’s Candies

78 E. Park Street

This wall sign on the east side of the Imperial Block advertises Sweet’s Candies, a Salt Lake City company that kept early Butte walldog Frank G. Meinhart busy decorating walls with ads for their products. How do we know? He was a rare sign painter who signed his work. According to his obituary, Frank G. Meinhart came to Montana from St. Louis when he was a young man, and lived and worked in Butte in a shop at 119 South Main Street until about 1927, when he and his wife moved to Hamilton. There he began accumulating land in the Bitterroot Valley and the Big Hole Valley. He drowned at the age of 73.

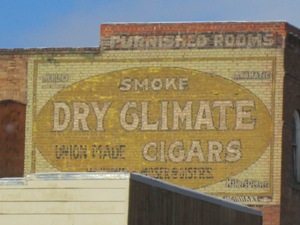

Two of his signed projects remain with his name and this is one of them. The other is the Smoke Dry Climate Cigars sign on the south side of the Alano Club at 721 S. Utah Street.

Sweet’s Candies is another regional or national company that took advantage of the fact that at its peak nearly 100,000 souls populated the streets of Butte 24 hours a day. Coca Cola, cigars, chocolates, whiskey all vied for premium real estate on the walls of Uptown Butte with the hope of capturing the attention of potential customers on the streets below. Sales must have benefitted as a result of Sweet’s marketing approach because they are still in business in Salt Lake City — www.sweetcandy.com.

For more images of Butte signs painted by Frank Meinhart, visit this blog — cindyinhelena3.wordpress.com/.

Meinhart at work painting a Sweet’s sign over top a Rex Flour sign.

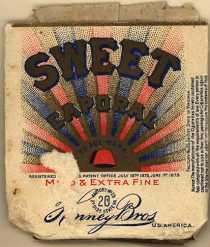

20. Sweet Caporal Cigarettes

78 E. Park Street

Sweet Caporal was one of the oldest names in cigarette brands that only ceased production in 2011.

The brand was originally produced by the Kinney Bros. Tobacco Company, New York, beginning in 1878, and became very popular. Kinney Bros., which was merged into the pre-1911 giant American Tobacco Company.

When the American Tobacco Company’s monopoly was broken in 1911, the Sweet Caporal trademark was retained by the restructured company.

One of the brand’s distinguishing features was the inclusion of collectible “cigarette cards” in each pack. Sweet Caporal cigarettes pulled its Honus Wagner card from the market in 1915 after the slugger complained he didn’t want kids to see him associated with tobacco products.

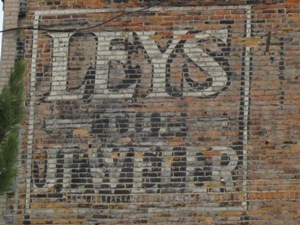

21. Leys The Jeweler

20 N. Main Street

According to Kim Kohn, Leys Jewelry was founded by James Leys in 1890 at 2 N. Main Street. In 1891, David Leys, James’ brother, joined the business. David took over the business in 1893, when James left Butte that year for New York City. Alexander Christie also joined the company that year. The store moved in 1908 to 32 N. Main St., and finally in 1912 to 20 N. Main St., where it remained until it closed in 1963. The sign located to 20 N. Main St. was most likely painted in the 1920s.

Ley’s partner Alexander Christie soon extended his interests into furniture on West Broadway and transfer and storage businesses in the warehouse district.

This precious privelege sign. which is fading fast on the south wall of 20 N. Main Street is an excellent candidate for restoration in its original black and white colors before it disappears forever as the one for the Red Boot Company which has become illegible and disappeared on the south wall of the Rookwood just next door.

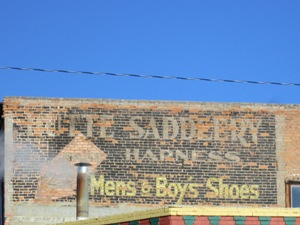

22. Butte Saddlery

28 S. Main Street

This sign still visible on the side of the Pincus Building alerts travelers to a once busy business tending to the tack needs of horses used to haul goods throughout the Hill. Before automotive trucks and trolleys, horsepower

One unlikely story is that Dublin Gulch was actually first named Doubling Gulch because it was where horse teams were doubled to haul their freight up the steep mountain to Walkerville. Several of the main streets in Uptown Butte such as Granite, Park and Montana were built to the specifications that would allow a team of horses and a wagon to turn around without backing up.

This sign is a fading reminder that everything in Butte before the automobile and truck was delivered by horse-drawn wagons and teams wrangled by teamsters, creating a huge demand for tack, livery, and other services related to horse-drawn conveyance.

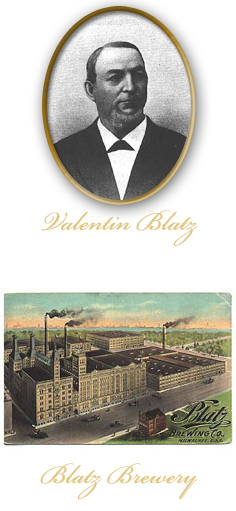

23. Silver Dollar Saloon/Blatz Beer

133 S. Main Street

According to the brewery’s corporate history, Blatz was one of Milwaukee’s finest breweries and the first to market beer nationally. It was founded by John Braun in 1846, originally called the City Brewery. The City Brewery produced about 150 barrels of beer a year until 1851 when Valentine Blatz, a former employee, established a brewery of his own next door. Braun died later that year and Blatz married his widow and merged the City Brewery and his own operation. At the time of the merger the combined breweries produced 350 barrels a year which rose by 1880 to 125,000 barrels. Blatz soon set up distribution centers in Chicago, New York, Boston, New Orleans, Memphis, Charleston, and Savannah and his brewery grew to include a bottling plant, a carpenter shop, railroad cars, cooper shop, machine shop and coal yard.

In 1890 Blatz sold his brewery to a group of London investors, who continued to operate the plant until Prohibition. Following Prohibition’s repeal, the Blatz brewery resumed operation, producing over a million barrels a year during the 1940s and 1950s. Its labels included Blatz, Pilsener, Old Heidelberg, Private Stock, Milwaukee Dark, Culmbacher, Continental Special, Tempo, and English Style Ale.

Now home to the Silver Dollar saloon, this building was built by the partnership of Grady and Gay and first served as a saddlery and carriage house. The building that wears the Blatz logos now was built on the cusp between Chinatown and the red light district. Main Street was the dividing line between Chinatown and the red light district, but there was substantial interaction between the two. A good example is the building attached to the Silver Dollar Saloon on Mercury Street. It was a brothel called The Lucky Seven, which also served as a boarding house for Chinese. Another example was the brisk business done by noodle parlors making deliveries of hot meals to the nearby Red Light District.

Where the Silver Dollar is was the first purchased plot of the newly chartered Butte City. The surveyor, guessing that the plot would become the center of the new city, bought it himself. He was close. The center of the Uptown evolved two blocks to the north at Park and Main Streets, and the Silver Dollar’s location became the edge of the commercial district.

Today, the Silver Dollar Saloon is one of the most popular watering holes in Butte with live music regularly scheduled that includes some of the most popular blues, zydeco, bluegrass and rock bands in the region on their stage.

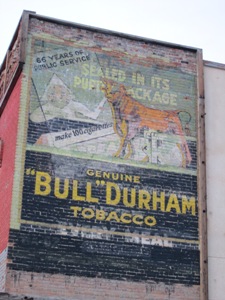

24. Bull Durham

Walkerville

According to the Duke University Libraries Digital Collection, the Bull Durham brand originated from an incident as the Civil War ended near Durham, North Carolina. Soldiers from both sides raided a farmer’s tobacco crop as they waited for surrender to complete. After the war, former soldiers wrote to the farmer, Mr. John Green to ask for more of the cherished tobacco. He obliged and soon the tobacco, named Bull Durham in 1868, became the largest selling tobacco brand in the world.

As evidence of the brand’s long reach and popularity, this sign was painted onto a wall in Walkerville, Montana. It was only recently uncovered when the owner peeled off the siding and found the sign on the brick wall that had been trapped beneath for decades.

Planning a visit to Butte soon?

If you would like to tour these signs when you are in the vicinity, you can use the information here for a self-guided excursion on the streets of Butte. Also, you can also arrange for a tour guide to show you these and other historic sites in Uptown Butte.

Guided Walking Tours — www.buttetours.info

Guided Golf Cart Tours — www.uptownbutteworks.com/tours.html

Looking for more information?

For a brief history of these signs and their historical significance, visit this story by former Mainstreet Uptown Butte Executive Director Kim Kohn — mtstandard.com/news/local/article_4dcf0eaf-0d63-5018-8bbe-b7e54d9aca0f.html.

For a photographic inventory of these Butte signs, visit the site of Dr. Ken Jones — www.drkenjones.com

And see additional images here of Butte ghost signs by photographer Elisa Renouard — www.veraldirenouard.com/gallery2/v/ghostsigns/

Similar ghost signs in Philadelphia — ghostsignproject.com/

Printed studies:

Fading Ads in New York City, Frank H. Jump, The History Press, 2011

Ghost Signs of Arkansas, by Cynthia Haas and photographer Jeff Holder, U of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Ghost Signs: Brick Wall Signs in America, by William Stage and Arthur Krim, Floppinfish Pub Co., 1989.

Much appreciation is acknowledged to the BSB Historic Preservation Office, Montana Main Street Program and the Montana Department of Commerce for their support for this project.

Also, as with all research related to Butte history, thanks to the work of the Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives to keep historical records readily available to the public.